Growing Old but Not a Granny

- 1.Growing Old but Not a Granny

Granny? Really? Who are you calling granny? In one of Shakespeare’s most famous lines, Juliet asks Romeo, “What’s in a name? What we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” As more than 10,000 baby boomers cross the “growing old” threshold of age 65 daily, they are challenging traditional ideas about growing old, including what they call themselves. Apparently, there is more in a name than what Juliet thought. And there’s an app for that. Don’t want to be called granny? Use your iPhone to check out Apple’s Grandparent Nickname app. Or, if you’re old school, you can now buy a book with all the more modern, hip versions of grandparent nicknames.

The “me” generation is once again rebelling against the status quo. They once expressed distrust of anyone over 30 years old. They sang along with The Who talking about “My Generation” not growing old and wondered along with The Beatles “will you still need me when I’m 64.” Now, it seems they’re leading another cultural revolution as the baby boomers face their own aging process and looming mortality, and that cultural shift impacts other facets of their lives, including approaches to health care and defining what “senior” means both in their own minds and in relation to other generations.

Many who work to provide care and services for an aging population often struggle, for instance, with exactly what the right words are to describe those who are our clients. Should we refer to them as seniors or senior citizens? As elderly? As older adults? Well, it turns out there’s no one-size-fits-all terminology that’s accepted within the population that’s 65 and over either. Marketing firm Varsity Branding recently published a white paper that includes results from a study that asked about seniors’ reactions to different words such as “senior” and “retirement.” What Varsity learned is that there are at least three distinct generational segments among the 65-and-older crowd. Varsity calls these three categories the GI generation, the transitional generation, and the baby boomer generation. As you might expect, their reported reactions to the terms “senior” and “retirement” were quite distinct.

Study participants from the GI generation are proud to be called seniors. They feel it’s a title of respect and honor. Similarly, the GI generation’s reaction to the term “retirement” is one of satisfaction and accomplishment—it’s a happy time in their lives. The transitional generation, as Varsity describes, wasn’t really thrilled with the term “senior,” yet they also weren’t offended by the term. The transitional generation also doesn’t mind the term “retirement,” but they also make a distinction between retiring from a job rather than retiring from a lifestyle. With the baby boomers’ responses, we see a drastically different perspective from that of the GI generation. The baby boomers think of the term “senior” as having negative connotations, and they don’t want to have that term used to describe them (unless, as Varsity says, they’re “in Wendy’s”). And retirement? The baby boomers don’t really recognize that word as it applies to their lives; they see it as a “foreign term” according to Varsity.

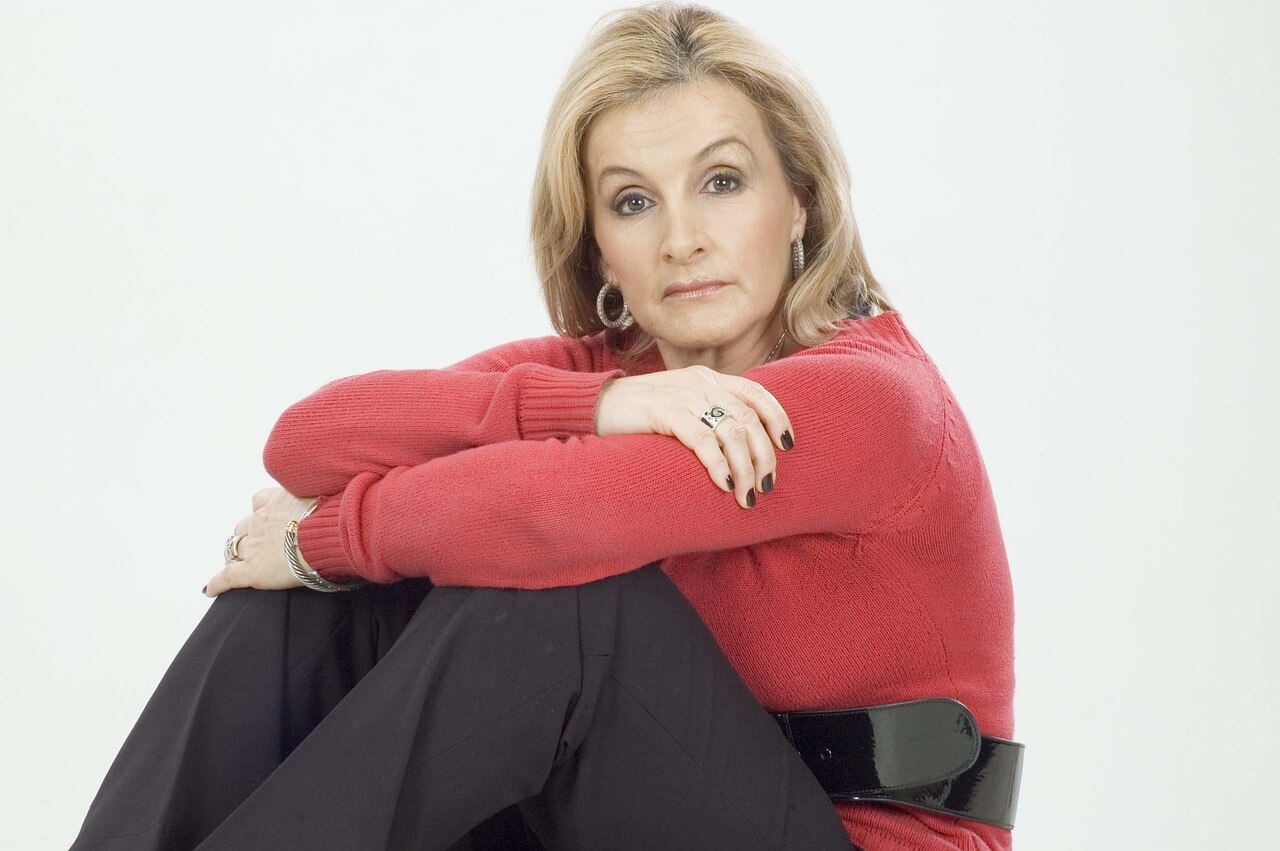

Does it matter that we’re seeing these differences in attitudes towards aging? How each generation sees themselves, their roles in society, their legacies, and their lifestyles makes a huge difference in their corresponding expectations about aging, interactions with other generations, and approaches to health care products and services. The GI generation and the baby boomers have experienced vastly different worlds. As Adair Lara writes in her article published at www.more.com, “’Grandma’ is my mother’s mother, with her white braid wrapped around her head.” Culturally, we’ve connected the name “grandmother” with a quaint, dowdy old lady. Lara—a grandmother herself—defines “the new G-Mother” as having “short red hair, a Mini Cooper, frequent-flier miles, and an iPod in her Kate Spade bag.” Lara also reveals what many modern-day grandmothers are feeling when she says she and her husband have goals and plans that don’t include babysitting.

The approach of the GI generation and the baby boomers are different for many reasons, and some of those reasons may be rooted in the fact that medical advances have given us the opportunity to have a better quality of life for a longer period of time. While the first joint replacement operations weren’t performed until the 1960s, they’re now commonplace, keeping many more people youthful on the golf course and tennis courts. We’ve gained ground in detecting some diseases earlier and preventing others. Life spans are longer as we’re living, on average, about 10 to 20 years longer than people did even 50 or 60 years ago. Those very real changes in health care along with an increased focus on exercise and eating well have made possible the new “G-mother” in many respects. As much as the baby boomers may want to rebel against the aging process, though, there is ultimately no avoiding growing old, and the reality of the baby boomers’ aging process may be contradictory to the self-image they prefer.

Next month, The Springs at Simpsonville takes a look at how baby boomers are actually faring health-wise as an aging generation and at the changing cultural dynamics resulting from the baby boomers’ image of aging versus traditional expectations.